Not just a pretty face... how emojis can end up as evidence in court

Posted on Jun 24, 2022

It’s fair to assume most of us would have used 👍 to signal agreement or 🎉 congratulate someone on their birthday. Indeed, emojis have become a natural way to either emphasise or soften our written messages. But as the use of emojis becomes increasingly common in communications - both personal and professional - it’s no surprise that lawyers are increasingly tasked with interpreting their meaning in a legal context and evaluating their potentially legally binding nature.

Can emojis be used as evidence?

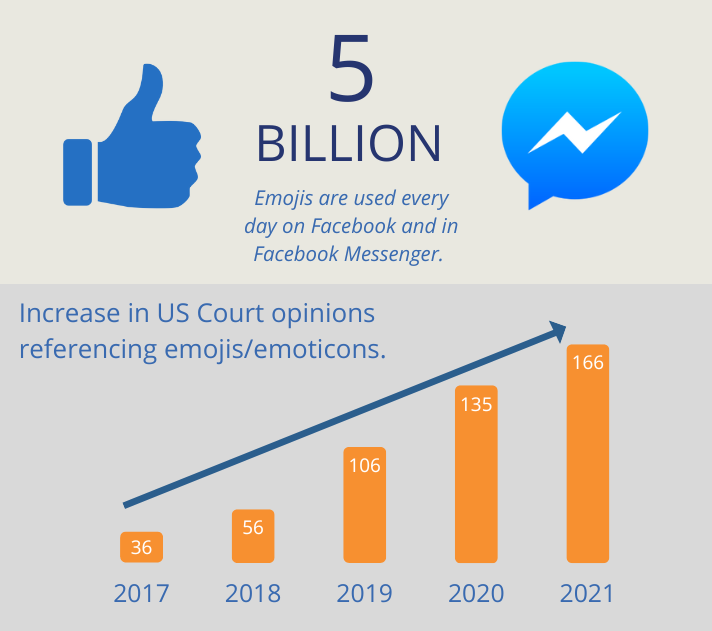

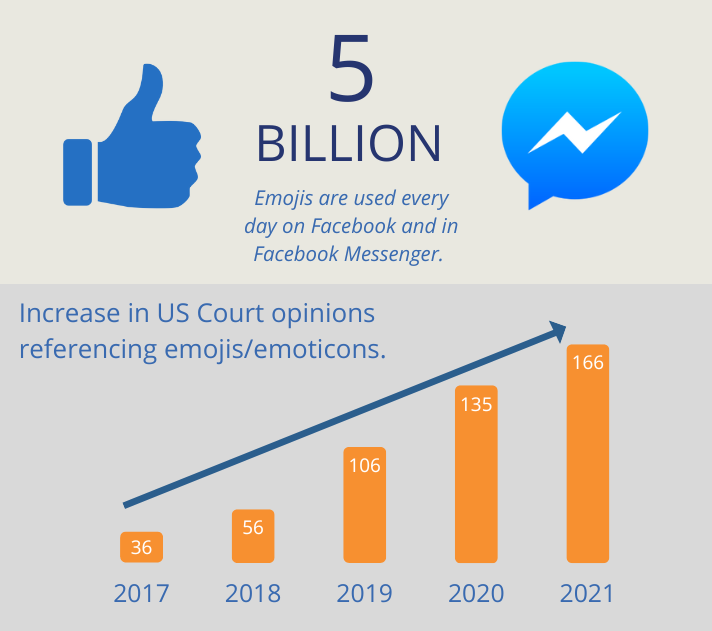

Far from being a fad, emojis are a language for the digital age. Lawyers, judges and juries are encountering them with increasing frequency in legal proceedings ranging from criminal trials to contract disputes. This is unsurprising given the rate at which emojis are used in electronic communications – every day more than 5 billion emojis are used on Facebook and in Facebook Messenger. In the US, the number of court decisions referencing emojis and emoticons are increasing each year with 166 cases in 2021 and other countries are following suit.

Every day more than 5 billion are used on Facebook and in Facebook Messenger

Despite some experts claiming that emojis are the first truly global language, the reality is that use and interpretation of emojis vary significantly by country. The challenge for the law is finding a consistent and reliable approach to evaluating communications using emojis. But as the scenarios discussed in this article demonstrate, this is far from an easy task.

Do “festive” emojis demonstrate intent to contract?

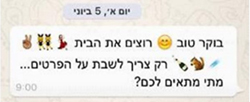

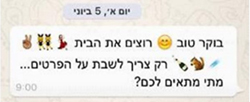

An Israeli court case involving a dispute between a landlord and prospective tenants illustrates the difficulty in determining the intent underlying the use of emojis. The landlord had listed his apartment for rent online and received a text from a couple which included the words “Good morning interested in the house just need to discuss the details ... when suits you?” The text also included a series of playful emojis interspersed with the text – a smiley face, a champagne bottle, a chipmunk and dancing playboy bunnies.

The landlord interpreted this text to mean the couple wanted the property and removed the listing. When the couple did not proceed, the landlord sued them. The judge devoted a paragraph in his judgment to the meaning of emojis in contractual negotiations, concluding that the couple had negotiated in bad faith by including “festive” and “smiley” emojis in their series of texts with the landlord. The judge ruled the couple must pay the equivalent of USD $2,200 to cover the landlord’s damages and legal fees.

This decision has been widely cited to illustrate the significance of emoji use in business negotiations – particularly the scope for these to be interpreted differently by the parties involved.

Other resources you might like:

- [Insight] Social Media and Its Impact on Trials

- [Insight] Legal Ethics and Social Media

- [CPD Course] Virtue and the Virtual: Introduction to Legal Ethics and Social Media

Can emojis amount to a criminal threat?

There have also been a surprising number of cases where emojis have either been found to exacerbate a criminal threat, or amount to a threat entirely on their own. In one notable US case, two men were arrested for making threats and stalking after sending a Facebook message which only consisted of three emojis – a fist, a hand pointing, and an ambulance.

The police interpreted the emojis as a threat that the victim would be beaten up (the fist), which would lead to (hand pointing) them being hospitalised (ambulance). However, the context in this case was critical – the two men had already been accused of assaulting the victim in his home one month before the message was sent.

Since this arrest in 2015, there have been a number of other cases around the world involving the use of emojis and how these modify or aggravate a criminal threat. Some of these involve more obvious emojis like guns or knives and bombs. But others involve seemingly innocuous emojis like aeroplanes – such as the case in 2017 where a New Zealand man was sentenced to 8 months in jail for stalking after sending the message “You’re going to f***ing get it” followed by an aeroplane emoji to his ex-girlfriend.

The defendant, in this case, had followed his ex-girlfriend around New Zealand after she had repeatedly tried to leave him, and conceded the emoji was a threat he was “coming to get her”.

The common thread in all these cases is the importance of context provided by the surrounding circumstances. In most cases, the actions of the defendants prior to sending the messages shaped the interpretation of the emojis by the police and the courts.

What is the situation in Australia?

So far there have only been a handful of cases where Australian courts and tribunals have considered the significance of emojis.

Burrows v Houda is the first Australian case to confirm that an emoji is capable of defamatory meaning. Houda reshared a tweet linking to an article suggesting that Ms Burrows may be referred to the NSW law society for disciplinary action. Another person replied to the post saying "July 2019 story. But what happened to her since?" to which Houda replied with only a zipper-face emoji. The District Court of NSW stated that the emoji implies that the person knows the answer but is forbidden or reluctant to talk about it. Therefore the emoji implied that Ms Burrows had engaged in improper conduct as a lawyer, and was defamatory.

In Re Nichol, the Supreme Court of Queensland had to consider whether an unsent text message signed off with a smiley face emoji constituted a valid will. The court found the text was a valid will, despite the informal nature of the smiley face emoji.

Interestingly, it was the absence of emojis from an employee’s Facebook post which shaped the Fair Work Commission’s interpretation of the facts in Singh v Aerocare Flight Support. In this case, an employee claimed he had been unfairly dismissed after posting a sarcastic comment “We all support ISIS”. The Commission concluded the post did not have the look of sarcasm, partly because no emojis were used in the post.

What's next: interpreting emojis consistently in legal proceedings?

With over 66% of Australians already using emojis in their everyday communications, it's likely we will see even more cases involving the use of emojis. The courts may adapt to these developments by making new rules and practice directions, or even in admitting expert evidence on the meaning of emojis for certain matters. It will be interesting to see how the law adapts to this new and growing form of digital communication in years to come.

Editor’s Note: This post was originally published in July 2018 and has been updated for accuracy and comprehensiveness.